Combatting Racism in the Restaurant Industry

The reckoning of racial inequity happened. Now what?

The racial unrest of 2020 – from the high-profile killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor to anti-Asian hate fueled by the pandemic – resonated among businesses but struck hospitality like no other industry.

Chefs, restaurateurs, nonprofits and big brands stepped up to combat inequity. The industry looked inward: pledges of inclusivity were made, mission statements changed and even diners contributed by supporting fundraisers.

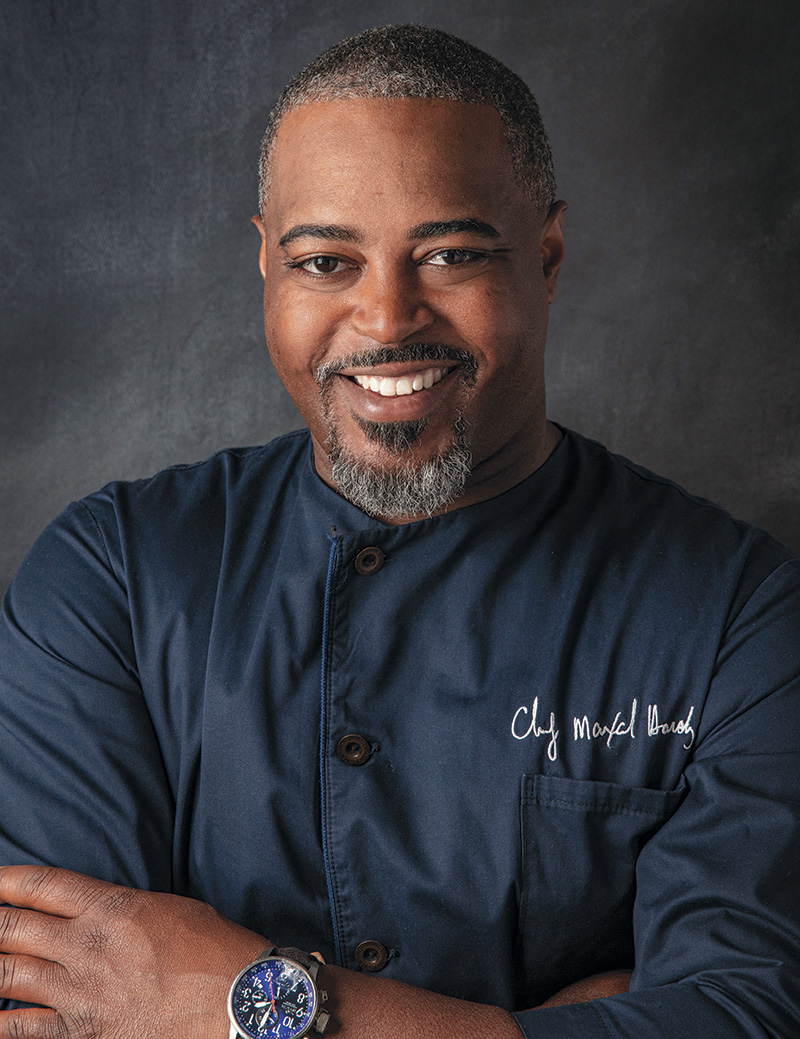

“The spotlight is a wonderful aspect of the shift, but the support from brands that we’ve supported our entire career has been the best part,” says Detroit-based chef Max Hardy.

But how does inequity remain a focus as a new year approaches and the industry is plenty ready to have the economic devastation of the pandemic in the rearview mirror for good?

It begins, operators say, by addressing the causes, including systemic racism. Consider, for example, that the average startup capital for white entrepreneurs lands around $106,720 compared with $35,205 for Black entrepreneurs, according to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Black restaurateurs say the statistics shouldn’t be surprising, considering that people of color have far less access to professional and financial resources. The economic divide, in part, can be attributed to the perpetual erasure of Black voices.

“To combat this, we must continue working with each other and using our voice in social media, during events and just using every avenue possible,” Hardy says.

“To combat this, we must continue working with each other and using our voice in social media, during events and just using every avenue possible,” Hardy says.

Pastry chef Paola Vellez, for example, has been using her Instagram feed, @smallorchids, to share her visually striking and creative sweet creations, but she also regularly posts about inequality to her 24,000 followers. Recently, she challenged the Latino community to support Haitians crossing the U.S. border saying, “I know some of y’all don’t want to hear this, but Haitians are Latinos ... Stand up for each other and make the Latino community inclusive for all.”

Once businesses acknowledge the inequity, they need to put in practices that support true inclusion, from hiring and promotions to treatment of workers and purchasing decisions, Hardy says. Creating or revising a mission statement is a start.

Once businesses acknowledge the inequity, they need to put in practices that support true inclusion, from hiring and promotions to treatment of workers and purchasing decisions, Hardy says. Creating or revising a mission statement is a start.

The James Beard Foundation, best known for its prestigious awards, realigned its mission statement last year to better reflect inclusion. It audited its procedures and policies to remove “systemic bias” and increase the diversity of those who vote for the awards.

“There’s so much to be done to help the community build back in ways that address the issues exposed by the pandemic and the national reckoning of race and gender,” says Clare Reichenbach, the foundation’s CEO at the JBF awards ceremony in September. “…The new standards of our industry must include equity, sustainability and working conditions where all can thrive.”

Reichenbach added that the lens of inclusion and equity would influence and determine future grants, educational programs and the awards.

Reichenbach added that the lens of inclusion and equity would influence and determine future grants, educational programs and the awards.

Combating lack of access will also increase equity. Nonprofit Black Food Folks is funding Black-owned businesses, while the Dipping Spoon Foundation is awarding full scholarships to women of color to attend culinary school.

“The importance of representation for BIPOC (Black, indigenous people of color) in this industry is vital and access is where it’s at,” explains Dipping Spoon founder Charity Blanchett. “There are some systems in place where some may not be able to utilize their craft based on someone else’s beliefs.” Blanchett emphasizes the importance of evolution for the restaurant industry, creating connections between racial injustice and the climate crisis. “The best people to reach out and talk to about how to cultivate the land moving forward is Black and indigenous people. The industry needs a breath of fresh air. They need our culture, our expertise.”

Says Hardy, “…the best way is to have mentoring programs, setting up culinary scholarship programs for aspiring chefs and starting culinary programs in high schools.”

For their own part and for others who want success, Hardy and Blanchett underscore the importance of learning, whether it’s in a formal classroom or taking on new experiences.

Hardy worked as the personal chef to NBA star Amar’e Stoudemire, formerly of the New York Knicks, before opening his own restaurants, two of which are under development.

Says Blanchett: “I believe that life is one big education credit.”

To keep the momentum moving, Hardy encourages people to reach out – people want to help.

“The advice I offer most is to keep learning, honing your skills and learning everything the industry has to offer,” Hardy says. “Join different organizations to help and support your growth.”

And for everyone, including peers, Hardy offers this. “When traveling or in your own city, research Black/POC chefs and restaurants. You are supporting an entire community. (By) supporting the locally owned restaurant, the chef and the employees, you’re supporting someone’s dream to provide their neighborhood with a quality menu.”

Blanchett agrees. “To facilitate the growth of the world we want to live in, we have to work together. We have to listen with all five senses,” she says.

“I’m excited for the new world we’re creating. The new world wants us as much as we want it.”

HOW TO KEEP THE MOMENTUM

Acknowledge the inequity at all levels of foodservice

Collaborate and work with the community using access, clout and your own audience at every touch point, from social media to everyday interaction

Examine your own culture, hiring practices, promotions and purchasing to ensure inclusivity

Foster mentorship for marginalized workers

Support nonprofit organizations committed to equal access and success for people of color