CHEF JOSÉ ANDRÉS: REFLECTIONS FROM THE PAST PROPEL THE FUTURE

► No other individual in food has accomplished more than José Andrés over the past decade. But it didn’t start out that way.

He was fired from El Bulli in 1990 for showing up late to an appointment with then-boss Ferran Adria. To this day, Andrés insists he was on time.

It was a low point in his life that he now sees as a lucky moment – because it pushed him to move to the U.S. and start again.

By 1993, Andrés became part of the team that opened Jaleo in Washington, D.C. Now, nearly 30 years later, his company, ThinkFoodGroup, runs 30 restaurants across the U.S. But perhaps more notably, in 2010, Andrés founded World Central Kitchen (WCK), a nonprofit that feeds people around the world in the wake of emergencies. The organization has set up relief operations across the U.S. and in more than a dozen countries – including Ukraine, where WCK was one of the first organizations on the ground this year. Wherever Andrés lands, droves of chefs volunteer to help. Many host fundraisers, donating the proceeds to WCK. Supporters include Jeff Bezos, who contributed $100 million when naming him a recipient of his new Courage and Civility Award.

Earlier this year, Andrés convinced the White House to host its first food summit in more than 50 years. The event will take place this fall; topics on the table could affect all parts of the food industry.

With so much on his proverbial plate, how does the chef balance being a dad, husband and leader of a huge restaurant group while trying to save the world?

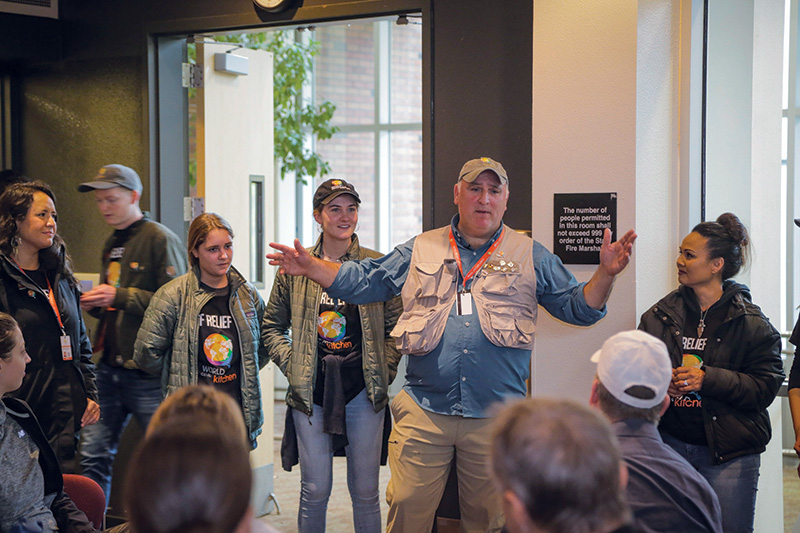

We recently sat down with him at his Jaleo restaurant in Chicago before he hosted a special dining experience for customers of Capital One bank. The following is an edited transcript of the chat, covering a variety of topics from industry issues and technology to finding common ground on today’s most challenging food issues.

”THAT TELLS ME THAT WHEN WE UNITE, THE FOOD COMMUNITY CAN BE A BIG FORCE OF CHANGE”

—Chef José Andrés

ME: You’ve spent much of this year so far working to feed displaced people from Ukraine. What’s the best way for food industry folks to help?

JA: Raising money, at the end, is the key. Sometimes the situation and the conditions are hard. We had some chefs who came to our main kitchen just outside Ukraine, and that was great. (But we also) have 500 restaurants in Ukraine that we support financially, so any dollar that anyone can give helps; but I know the industry here has gone through a very hard time, so I’m not expecting anything.

ME: You’re chairing the first White House Food Summit since 1969, which produced groundbreaking advances in school food and feeding programs like SNAP. What topics are on the table this time?

JA: School lunches, food deserts and food insecurity, too. My perfect idea is to have a true food advisor to the president, who is not out of the USDA or FDA. They’d be an advisor, the same way you have national security advisors or defense advisors or a national science advisory board.

ME: What do you think of new food technologies like CRISPR that aim to do things like take bitterness out of mustard greens, so more people will eat them?

JA: I think the world is a better place today because over the last hundreds and thousands of years, somebody always tried to push for something else. More of these things, I think, are not bad. But only the really good ideas will survive. I myself am supporting or investing in the growth of fish cells to produce salmon (and) the growth of meat cells to produce meat. But I’m not against eating salmon or meat. It just goes with my line of diversifying resources.

ME: Do you see Americans changing their diets to try to help the planet? Do you think that’s a growth area?

JA: I think it’s complicated. In the end, people want to enjoy life today, and that’s been true for a long time. People keep doing very dumb things, like smoking and drinking, even though it’s proven that you shouldn’t be drinking or smoking too much. So if we don’t really care what we are doing to our own bodies and to our own health, I have a hard time believing that humanity will care about anybody else. But I’m hopeful that America will care. We have to.

ME: You’ve faced a lot of bleak situations and pushed through. How do you keep your hope and motivation?

JA: We do it because we have to. I mean, what are you going to do? I missed the birthday of my daughters. I missed a lot of things (over) the last 100 days because I was coming and going to Ukraine. The last three years, I’ve been in Lebanon, and in fires in volcanoes.

Sometimes you wonder to yourself, “why am I doing this?” But then you hear the inner voice say, “I do it because I believe it is the right thing to do,” because my daughters are seeing an example in me of trying to fix things with action, not just with words. And because my wife encourages me to do it. I do it because it’s the only way you can inspire people to join and use their talents to help others.

But mainly, you do it because there may be people whose day began very dark, and when they see you, they smile because all of a sudden, you’re giving them a little glimpse of hope. That’s probably the main reason.

ME: So you have this partnership with Capital One bank where you are curating dining experiences at U.S. restaurants for its members. How did that come about?

JA: If this is something where I’m helping restaurants to move away from these COVID-19 times and start celebrating our cities, then it’s great. And even if it’s only the restaurants that are part of the programs in different cities with Capital One across America, it sends the message of "come on, guys, let’s get out of the house." I support anything making our streets full again, making our streets vibrant again and making the restaurants alive with people and celebration.

ME: What are the biggest lessons you take from the pandemic on how to make restaurants work?

JA: We need to value close family and friends and the people next to you. It came at a good moment for me, because (my daughters are) all going to university, and it was a way to bond with them more. It also taught me to value the people I work with, especially in the early days of the pandemic. From the moment they told me I had to close my restaurants, we put together a team of more than 3,000 restaurants in North America. We were the biggest restaurant company out there for a few months, covering local needs in a lot of places. And that felt really good.

ME: You opened new restaurants in the last few years rather than shrinking. Any advice for other restaurateurs?

JA: I grew, but I had to close some restaurants, too. For six or seven weeks, we kept all the staff at all the restaurants on the payroll, and that depleted any money we had in the bank. That was a big decision. So the big learning and the growth is we have a lot of good, loyal people who have been with us forever. They stuck with us and kept pushing.

But I think this pandemic has shown all of us to be more resilient. We saw so much creativity and bending the rules of alcohol and cocktails to-go, and the local government overall adapted to allow us to take over the streets (for outdoor dining).

ME: So many chefs hang onto your every word. Is that a lot of pressure to feel people are listening to you?

JA: I don’t know if that’s true. It doesn’t feel that way to me.

ME: It’s true.

JA: Then we need to bring it down to earth.

ME: You often say, 'We don’t need higher walls, we need longer tables.' What does that mean?

JA: That you cannot be the holder of all the truth. Other people have opinions, and you need to find common ground. You also need to know where your limits are and what you are willing to accept. At the White House Summit, we’re gonna have a lot of issues. Will the food industry be able to feed itself? Will the farmers of America be able to feed themselves? The issue of the minimum wage for the restaurant industry? It’s complicated. Should everybody make a minimum wage that is also a living wage? Yes, totally. Now, how do we make it happen in a way that makes sense, and is good for everybody, and does not just increase wages for people in the front of the house, while wages for the kitchen stay low? That’s something we have to solve, because that creates an even bigger gap inside the restaurant. I’m not in favor of that.

So we need to be informed, learning and listening; longer tables, bring everybody in.