Lobster Is on a Roll

Lobster rolls are seeing a resurgence. But they’re more likely to be highly seasoned by wasabi or chilies than warm butter or mayo. Here are three twists on the traditional sandwich.

Lobster rolls might sound like a New England tourist trap, but they’re just as revered in the culinary landscape as any other indigenous seafood playing to local flavors.

Stretching past their homegrown borders, lobster rolls have hit the road. They’re more likely to be highly seasoned by garlic, wasabi and chilies than the standard warm butter or mayonnaise, and often served in bread that’s not the classic top-loading bun.

The iconic sandwich is so well received that it’s now worthy of its own segment, from Marc Forgione’s Lobster Press in New York and the Happy Lobster food truck in Chicago to multi-unit Luke’s Lobster (New York, Boston, Chicago and Las Vegas).

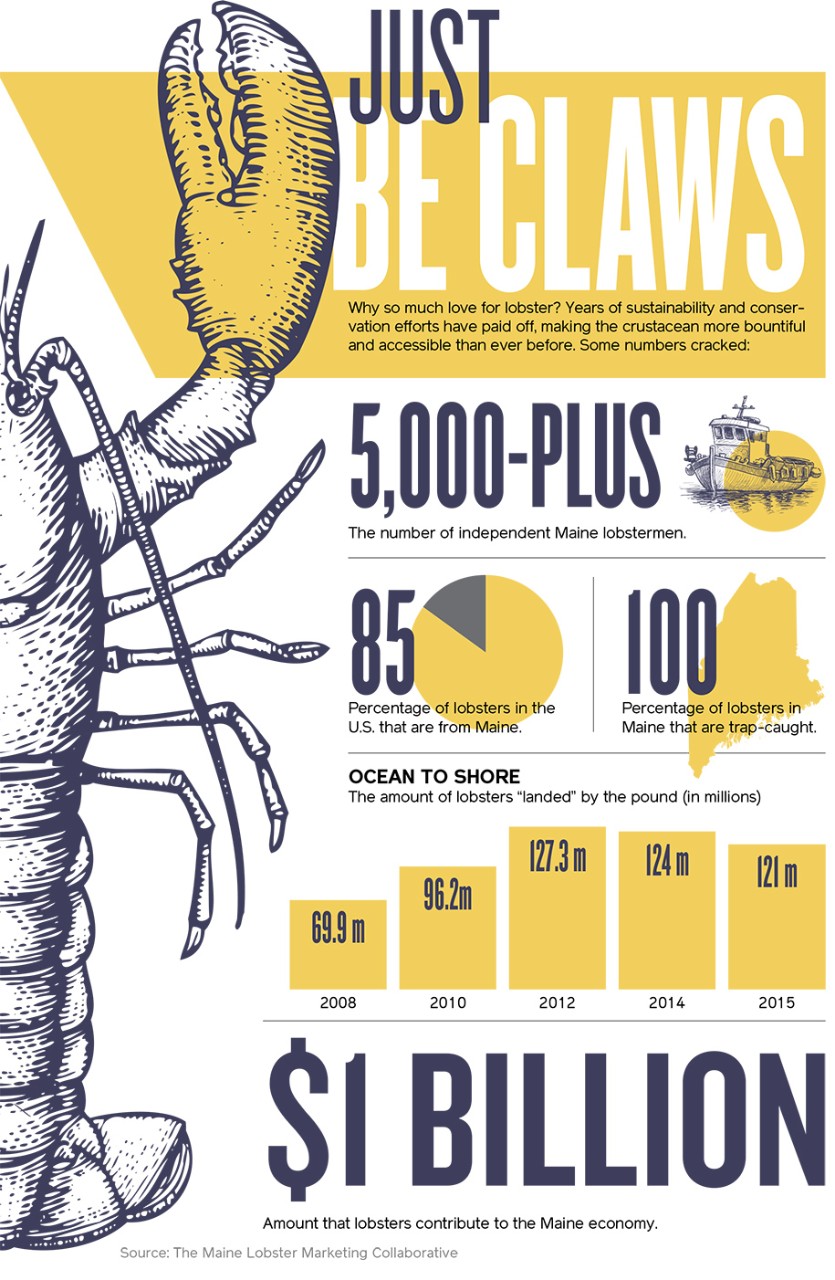

“The popularity of lobster rolls is certainly on the rise,” says Matt Jacobson, executive director of the Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative, a nonprofit organization that supports the industry. “We’re also seeing the rise of lobster in appetizers, primarily in the South and West regions of the U.S.”

Serving lobster on a roll creates a more accessible price point for a protein long perceived as a luxury food item. Diners willing to pay for quality see a $14 price tag as a gateway to tasting a food that may have been too expensive in the past.

Sustainably raised, cage-caught and hand-harvested, lobster’s abundance will likely continue. Here are three takes beyond the traditional.

A Thousand Lobster Rolls Later

As the executive chef at Neptune Oyster Bar in Boston, Michael Serpa saw more than 100,000 traditional lobster rolls come off the line. He knew he would serve anything but that version when he opened his own place in the city, Select Oyster Bar.

“A lobster roll is very one-dimensional flavorwise,” he says. “This sandwich (see recipe) is a little more interesting, has a better texture with the crispy bread, nice fat from the avocado and tomato mayo, but it still showcases the lobster. It also has a lot of acid, which I think helps the lobster shine more than covering it in pure fat.”

Word of caution: Lobster doesn’t cook evenly. So be careful not to overcook the claws and knuckle meat, which require less time. Serpa recommends cooling down the lobster on the counter because an ice bath can toughen the meat.

Classic on Classic

When you’re a chef born and bred in Maine—the state that provides the country with 85 percent of its lobster—it’s only fitting to put a lobster roll on the menu. But when you’re the executive chef at Colonie, a highly regarded restaurant in Brooklyn, New York, it becomes a classic on another level.

Executive Chef Andrew Whitcomb pays homage to his Maine roots by pairing the lobster with a remoulade of celery, a complementary lobster ingredient. Lobsters are broken down for the claw and knuckle meat while the tail is reserved for another use and the shells are for roasted for stock.

Of course, the bun is top loading and the sides are toasted, but spread with mayonnaise first—not butter.

From East to West

Mark Stark grew up on Solomons Island, Maryland, by the Chesapeake Bay, so he’s familiar with food fresh from the sea.

After starting in pastry, he became an executive chef in Seattle. Now the owner of six restaurants with his wife, Terri, in California, Stark’s approach highlights local seafood. But the lobster roll is all about Maine, with flavors that bring out the attributes of the crustacean.

For his lobster roll, it’s garlic butter and fennel balanced with plenty of acid to brighten and cut through the richness of the meat. His recipe was inspired by a past issue of the now defunct Gourmet magazine, depicting a bright summer day, easily eliciting an afternoon on the East or West coast.